South American, or Latin American cinema has a prestigious history. In the 50s and 60s directors such as Solanas and Getino reacted against the ‘golden era’ of the 40s with the international film movement of the Third Cinema – neither Hollywood-esque commercial product nor elitist arthouse. Third cinema was a political cinematic movement that co-joined the continents of Africa and South America and represented an attempt to film from the perspectives of the people who were under both political and economic imperialism by Europe and the USA. And there was, of course, the Cinema Novo in Brazil, represented by Rocha. But popular South American cinema of the 40s, turned another way – most significantly represented by the Mexican lucha libre free style wrestling movies of El Santo.

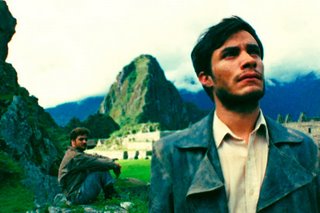

Motorcycle Dairies is definitely part of a renaissance of South American popular cinema. Along with such films as Ameros Perros (2000) directed by Alejendro Gonzales Inarritu; Y tu mama tambien (2001) by Alfonso Cuaron; and City of God (2002) by Fernando Meirelles, Carandiru (2005) by Hector Babenco, Motorcycle Dairies represents the cutting edge of what multinationally funded South American popular cinema can achieve. Inarritu has gone on to direct 21 Grams; Cuaron a Harry Potter episode and the excellent Children of Men; Meirelles, The Constant Gardener; and Salles is working on Kerouac’s On the Road. The hope must be that this does not constitute an relinquishing of their homelands.

Of all the films, Motorcycle Dairies has the closest relationship to Third Cinema, though the director Walter Salles has ‘hidden’ this within the film… specifically in the middle section when the camera is forced to go on the road with the travellers undergoing problems with limited crew, low light and bad weather; but also with the use of non-actors… the use of semi-still images avoids sentimentality, but also anchors the film in an historical dialectic, the people do not ‘play’ people from 1952, they are present now as ‘real’ people… and it is interesting that the political situation that gave birth to Third Cinema, also gave birth to Che Guevara – or rather – politicised the young Ernesto during his trip on a motorcycle around South America.

Eight years later, Guevara would write in his book ‘Guerrilla Warefare’:

‘The guerrilla band is an armed nucleus, the fighting vanguard of the people. It draws its great force from the mass of the people themselves.’

… and so does Salles’ film. Indeed, Salles began by making documentaries and is inspired by the documentary format in the fiction film. As he said in 2004 at the NFT:

‘I think I turned to documentary film-making very early on as a way to know a little bit more about my country and my roots... That's why I have always admired documentaries, because they open windows that can make you understand much better where you come from, much better than fiction, I think. So this was a really good place to start. I did documentaries for maybe 10 years before I turned to fiction films... I think fiction film-making is... deciding what is part of the film and what is not. The necessity to conceptualise has to come very early on, and defining a vector of development for that film also at the beginning of the process will allow you much more freedom as you go along. I don't believe in such a thing as a "locked" screenplay. On the contrary, I'm a strong believer in the necessity of imperfection coming into the film. But I also think that the more you reason collectively about what the project should be at the beginning of the process, the more you can improvise later.’

Labels: David Deamer, Motorcycle Dairies, South American Cinema, Third Cinema, Walter Salles

1 Comments:

Most of us know Che Guevara (if not his name, at the very least his face) from the iconic and much imitated t-shirt that seems to be an essential part of the wardrobe of a whole generation of (non-political) students. This image was taken, incidentally, by Alberto Korda, a long term supporter of Guevara. He didn't recieve a penny of royalties until he sued Smirnoff on 2000. He donated the entire proceedings to the Cuban healthcare system.

Back to the film.

What The Motorcycle Dairies does as a film for its subject matter is twofold. Firstly, it humanises Guevara, portraying the young man who existed before the revlutionary, before the bloodshed. It could be argued that this is not a good thing. Would such a film be acceptable if made about one of today's self-styled freedom fighters? Secondly, it puts together the pieces that formed the backbone of Guevara's ideals, the journey that turned him from a medical student to guerrilla fighter and insurgent. This, for me, was the most interesting part. Guevara has always been portrayed as, at best, misguided and, at worst, an enemy of the people. The Motorcycle Diary's narrates Guevara's realisation that the indeginous peoples of South America (and through common experences the indeginous people of the world) were all one people. In this light, Guevara's exportation of guerilla warfare and revolution into countries outside of Argentina are not led by power, greed and opportunism but political strategy. In true Marxist fashion, revolution in one nation is always tempered by concession, reforms, and counter-revolutions and so it was global communist revolution is the key to success.

Back to the film.

David talked in his introduction about the use of non-actors playing not characters from 50 years ago but themselves, now. A perfect example of this is the end sequence of The Motorcycles Diaries. Non-actors from thoughout the film are brought together for a series of shots that look initially like blask and white photographs in their composition and near stillness. And yet they breath, perseptively, and sway naturally as they stand. A beautiful and potent technique in a beautiful and potent piece of cinema.

Post a Comment

<< Home